Euclidean Distance

Euclidean Distance is the ‘ordinary’ straight line distance between two points in Euclidean Space.

It can be seen in action as the frustrating difference in distance between how far away something is (the straight line distance) and how far you have to go to get there (the rather disappointingly named distance travelled).

Conveniently for machine learning Euclidean Space generalises to high dimensional spaces (three dimensions would be a touch restrictive for most classification problems). However, as with most distance metrics its usefulness does tend to break down under the Curse of Dimensionality

Since we can’t get a ruler out and measure the Euclidean distances in n-dimensional space (although please do let me know if you manage to locate an n-dimensional ruler) we need to use algebra to calculate it.

This bit of algebra specifically:

\[d(x,y) = \sqrt{(x-y)^T(x-y)} = \sqrt{\sum_{i}(x_i - y_i)^2}\]Pythagoras

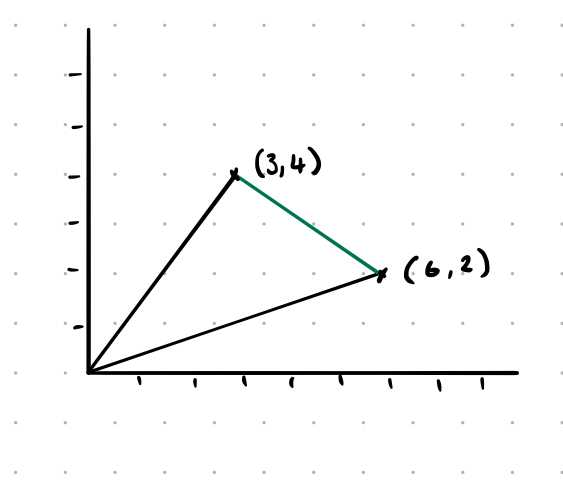

This complex and scary looking bit of maths breaks down to Pythagoras’ Theorem:

\[a^2 + b^2 = c^2\]

This works because each of these vectors is actually a right angle triangle1, and the dot product of a vector gives us the extent to which the vectors go in the same direction. So we’re just solving the green triangle.

Vectors

Let’s go back and look at why that works. (This bit is going to involve a bit more mathematical notation than the rest did.)

We’ve got some arbitrary vectors $a$ and $b$ of length $n$ and we want to know how far apart they are:

\[\begin{align*} a &= [a_1, a_2, a_3, ..., a_n] \\ b &= [b_1, b_2, b_3, ..., b_n] \\ \end{align*}\]We’re going to use this section of the distance function to work that out (or more accurately to prove that both ways of writing our distance function are equivalent):

\[d(x,y) = \sqrt{(x-y)^T(x-y)}\]Vectors are a single row matrix so “dotting” them with themselves is done in the same way as you do with a matrix2:

\[\left[ \begin{matrix} a_1 - b_1 \\ a_2 - b_2 \\ a_3 - b_3 \\ \vdots \\ a_n - b_n \end{matrix} \right]. \left[ a_1 - b_1, a_2 - b_2, a_3 - b_3, \dots, a_n - b_n \right]\]Terrifying, right? Just take the first item from each and multiply them together:

\[(a_1-b1).(a_1-b1) + (a_2-b2).(a_2-b2) + (a_3-b3).(a_3-b3) + \dots + (a_n-bn).(a_n-bn)\]We can simplify that again as something multiplied by itself is squared:

\[(a_1-b1)^2 + (a_2-b2)^2 + (a_3-b3)^2 + \dots + (a_n-bn)^2\]Which in turn can be reduced to the sum (add all the items together) of the squares of all the values from 0 to wherever ($i$):

\[\sqrt{\sum_{i}(x_i - y_i)^2}\]Which is where we started. Woohoo we proved Euclidean distance works.

Comments powered by Talkyard.