Math Notes: A Short Intro To Differentiation

Differentiation is the process of computing the gradient (derivative) of an arbitrary function and can be used in many simple cases to minimise a function describing the loss (error) of our model.

This is based on the premise that since the ability of a model to match a set of data cannot be better than perfect there therefore exists a cost function that has an absolute lower bound of 0. Our model will not usually be able to reach this lower bound (and in fact reaching it is frequently undesirable as it leads to overfitting) however, there will be some optimal value that get us as close as possible while still maintaining generalisability.

If the optimal values are changed even by a small amount the cost of the model will increase.

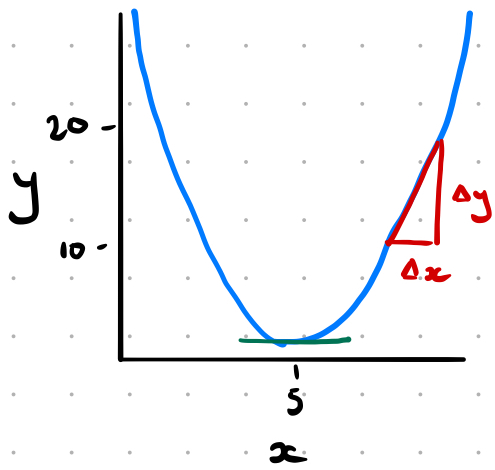

Figure 1

Figure 1

For example, in this simple case the value $x=5$ minimises the value of $y$.

The minimum point of a function that behaves in this way has a gradient of 0 which makes the process of minimising it a case of finding this point.

We achieve this by approximating the function as a straight line segment and calculating the gradient of that straight line. We then make the line shorter and figure out how the derivative behaves as the length of the segment approaches zero.

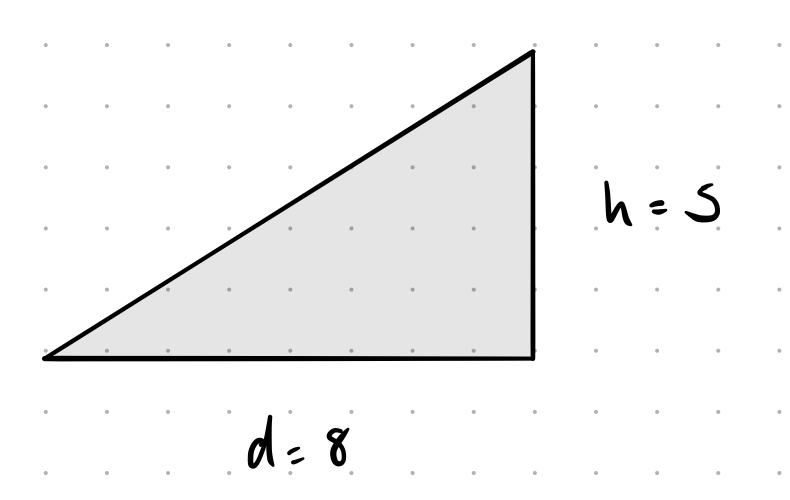

This whole process relies on calculating the gradient of a slope. Gradients are usually expressed as a simplified fraction: $\frac{height}{distance}$

\(Gradient = \frac{5}{8}\)

\(Gradient = \frac{5}{8}\)

Generalising

Using the red triangle in Figure 1 we define the gradient of the hypotenuse as $\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}$

At a general point $x$ therefore the gradient of a function $f(x)$ will therefore be:

\[m \approx \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{f(x + \Delta x ) - f(x)}{\Delta x}\]Note

$\Delta y = f(x+\Delta x) - f{x}$ as:

- $y$ is given by $f(x)$

- we are approximatingthe function as a line segment which is the bit between $x$ and $x+\Delta x$. This isn’t just $\Delta x$ as the value of $y$ is impacted by the value of $x$ not just the size of $\Delta x$

In order to improve this approximation we want to see how the gradient behaves as $\Delta x$ is reduced in size:

\[m_x = \frac{dy}{dx} = \lim_{\Delta x \to\infty} \frac{f(x+\Delta x) - f(x)}{\Delta x}\]where:

- $\lim_{\Delta x \to\infty}$ means “take $\Delta x$ to infinity”

- $m_x$ is the gradient of $f(x)$ as a function of $x$

- $\frac{dy}{dx}$ is a formal way of writing a derivative which implies the process of taking the limit

Examples

A simple one where we know m: $y = 3x + 2$, $m = 3$

\[\begin{align*} m_x = \frac{dy}{dx} &= \lim_{\Delta x \to\infty} \frac{f(x+\Delta x) - f(x)}{\Delta x} \\ &= \frac{(3(x+\Delta x) + 2) - (3x + 2)}{\Delta x} \\ &= \frac{3\Delta x}{\Delta x} \\ &= 3 \end{align*}\]We didn’t actually need to take the limit here as everything cancels out.

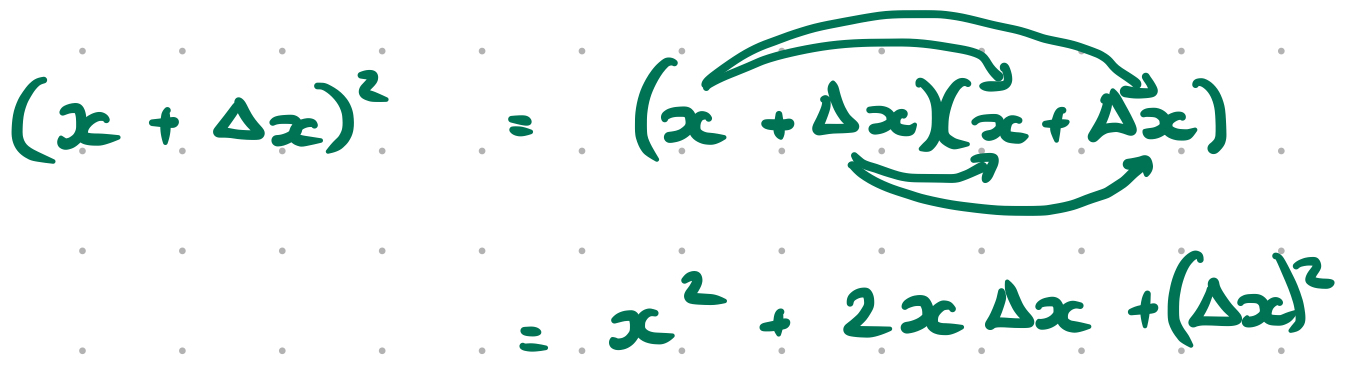

A more slightly more complex example is provided by $y = x^2$:

\[\begin{align*} m_x = \frac{dy}{dx} &= \lim_{\Delta x \to\infty} \frac{f(x+\Delta x) - f(x)}{\Delta x} \\ &= \frac{(x+\Delta x)^2 - x^2}{\Delta x} \\ &= \frac{x^2 + 2\Delta x + (\Delta x)^2 - x^2}{\Delta x} \\ &= \frac{2x\Delta x + (\Delta x)^2}{\Delta x} \\ &= 2x \end{align*}\]This is $2x$ because as $\Delta x \to 0 (\Delta x)^2$ becomes vanishingly small.

Note

Multiplying out brackets isn’t particularly complex but it can look a touch confusing. The best demonstration I’ve found of how to do it/why the answer is $x^2 + 2 \Delta x + (\Delta x)^2$ is this:

Comments powered by Talkyard.