The Curse Of Dimensionality

The curse of dimensionality refers to the fact that the properties of high dimensional space are weird and counter intuitive, and the higher the number of dimensions the weirder it gets.

There’s a few ways to demonstrate this, so we’re going to work through all of them.

- The distance between the corners and the centre

- The fraction of the volume of a hypercube occupied by its hypersphere

- The amount of the hypersphere occupied by its shell

- And finally the impact of all of this on distances

How far are the corners from the centre

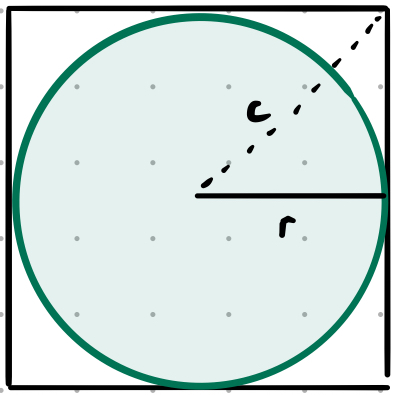

In 2-dimensions this problem is fairly trivial. If you have a square with sides $2r$ entirely enclosing a circle with radius $r$ you know that the faces are a distance $r$ from the centre of the square so you can use Pythagoras’ Theorem to work out the distance from the centre to the corners (or the distance from one corner to the other).

So for this triangle, assuming $r$ is of unit length1 ($r = 1$):

\[\begin{align*} c &= \sqrt{r^2 + r^2} = r \sqrt{2} \\ &= r \sqrt{2} \\ &= 1.414 \end{align*}\]When we translate this into 3-dimensions the corners of the cube are intuitively $\sqrt{r^2 + r^2 + r^2} = r \sqrt{3}$ from the centre.

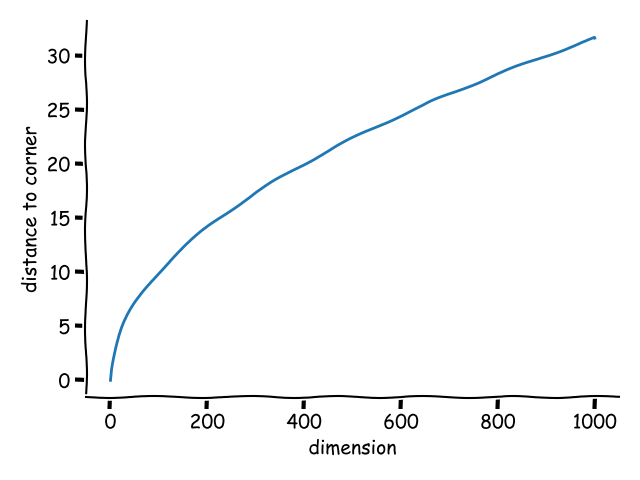

This pattern continues so that in n-dimensions a hypercube2 with sides of length $2r$ has corners that are $\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n}r^2} = r \sqrt{n}$ from the centre.

If we plot that we get:

The code used to generate this is available on GitHub.

This demonstrates that at high dimensions the distance to the corners of the hypercube becomes many times the radius of the hypersphere, so, although the sphere touches the cube in the centre of all it’s faces it never gets near the corners.

What fraction of the volume of a hypercube is occupied by its hypersphere?

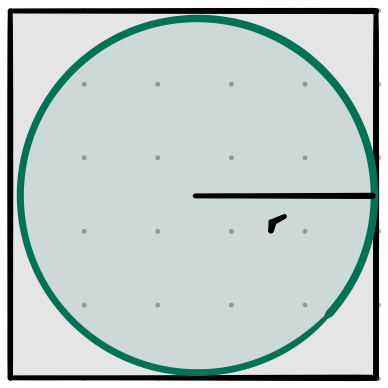

Going back to 2-dimensions:

A square of sides $2r$ has an area $4r^2 = (2r)^2$,

The enclosed circle has an area $\pi r^2$

\[Ratio_{square:circle} = \frac{A_{circle}}{A_{square}} = \frac{\pi r^2}{4r^2} = \frac{\pi}{4} \approx 0.785\]In 3-dimensions:

The cube has a volume $8r^3 = (2r)^3$

The sphere has a volume3: $\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3$

So the ratio is:

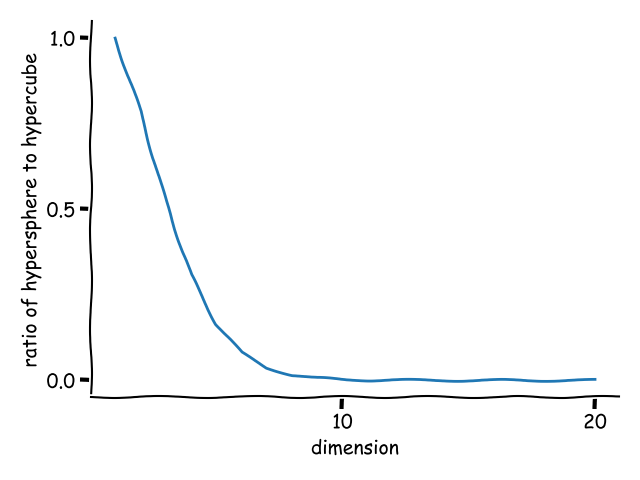

\[\frac{\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3}{8r^2} = \frac{4\pi}{3x8} = \frac{4\pi}{24} \approx 0.52\]This is a fairly substantial decrease, and when we generalise that to n-dimensions the difference becomes startling:

Volume of hypercube: $(2r)^n$

Volume of hypersphere: $\frac{\pi^{\frac{n}{2}}}{\Gamma(\frac{n}{2} + 1)}R^n$

NOTE:

- $\Gamma(x)$ is Eulers Gamma Function which extends the factorial function to non-integer arguments]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamma_function

- R is the convention for radius in this equation.

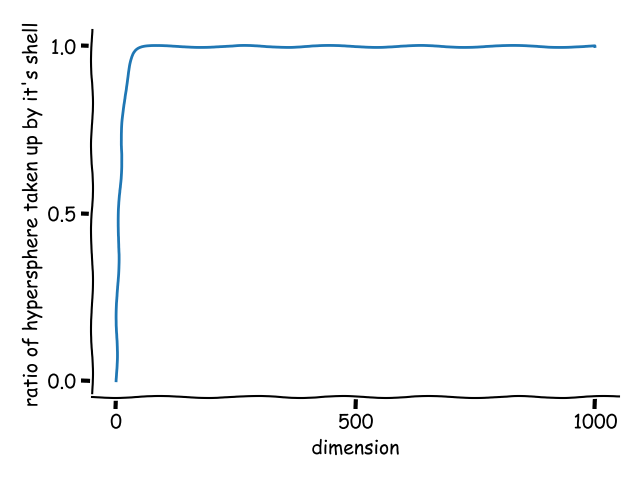

Plotting the hypersphere/hypercube ratio demonstrates that the volume of the hypercube taken up by the hypersphere rapidly drops to zero as the dimensionality increases. For this one you don’t need to go much above 10 dimensions to see the effect:

The code used to generate this is available on GitHub.

How much space does the “shell” take up?

We can construct a shell for the hypersphere by creating a second hypersphere inside the first so that the outer hypersphere has radius $r$ and the inner has a radius $r - \delta$ where $\delta$ is asymptotically4 smaller than $r$ ($\delta \ll r$).

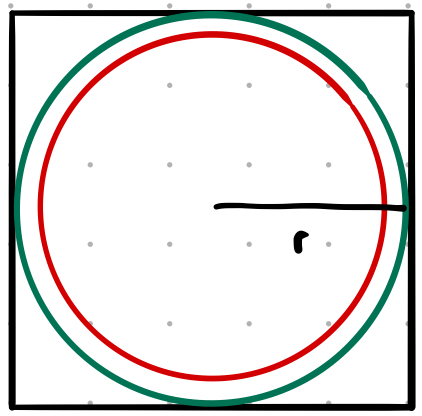

Back to 2-dimensions again:

The area of the green circle is $\pi r^2$ and that of the red is $\pi (r-\delta)^2$.

However what we are interested in, in this instance is the area of the shell (also known as the annulus):

\[\begin{align*} A_{shell} &= \pi r^2 - \pi(r-\delta)^2 \\ &= \pi(r^2-(r-\delta)^2) \end{align*}\]So, for a unit circle where $\delta$ is 0.1:

\[\begin{align*} A_{green} &= \pi * 1^2 &\approx 3.142 \\ A_{annulus} &= \pi (1^2 - 0.9^2) &\approx 0.597 \\ ratio &= \frac{A_{annulus}}{A_{green}} \\ &= \frac{0.597}{3.142} &\approx 0.19 \end{align*}\]So the shell takes up a very small proportion of the total area (which is what you’d expect). How does that compare to 3-dimensions?

Volume of outer sphere = $\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 \approx 4.189$

Volume of the shell = $\frac{4}{3}\pi(r^3 - (r-\delta)^3) = \frac{4}{3}\pi(1^3 - 0.9^3) \approx 1.135$

The ratio is therefore:

\[\frac{V_{shell}}{V_{sphere}} \approx \frac{1.135}{4.189} \approx 0.271\]Moving from 2 to 3 dimensions increases the amount of space the shell takes up but not significantly. Once again however things start getting weird as you increase the dimensionality:

Volume of outer hypersphere5 = $\alpha r^n$

Volume of shell = $\alpha(r^n - (r-\delta)^n)$

A a proportion of the whole sphere therefore the shell occupies a volume:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{V_{shell}}{V_{sphere}} &= \frac{\alpha(r^n (r-\delta)^n)}{\alpha r^n} \\ &= 1 - r^{-n}(r - \delta)^n \\ &= 1 - (r^{-1}(r-\delta))^n \\ &= 1 - (1 - \frac{\delta}{r})^n \end{align*}\]Taking the limit of this as $n$ tends to $\infty$ gives:

\[\begin{align*} \lim_{n\to\infty} \frac{V_{shell}}{V_{sphere}} &= \lim_{n\to\infty} 1 - (1 - \frac{\delta}{r})^n \\ &= 1 \end{align*}\]This is because $1 - \frac{\delta}{r}$ < 1 which results in most of the volume of the hypersphere being concentrated in a thin shell around its edge.

Plotting this demonstrates the speed at which the volume of the hypersphere becomes entirely contained within its own shell:

The code used to generate this is available on GitHub.

So? What’s your point?

TL;DR as the number of dimensions gets larger the distance between the points gets rapidly smaller.

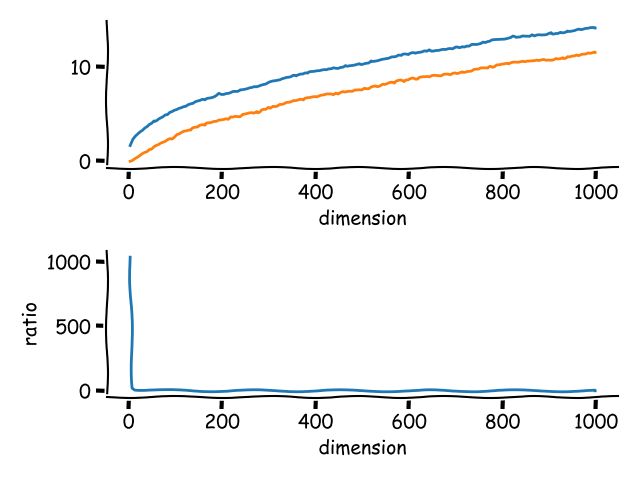

Visualisation:

- For a range of dimensionalities draw $10^4$ uniformly distributed data points6

- Compute the pairwise distances between the points

- Find the max and min distances between the points

- Compute the ratios of the range of distances with relation to the minimum distance: $\frac{(d_{max}-d_{min})}{d_{min}}$

- Plot the results

The code used to generate this is available on GitHub. WARNING: this will take several hours to run on a standard desktop machine.

This provides empirical evidence that in high dimensions the difference between minimum and maximum distances tends towards zero thus all distances become “similar”.

Or in mathematical notation:

\[\lim_{n\to\infty} \mathbb{E} \lgroup \frac{d_{max} - d_{min}}{d_{min}} \rgroup \to 0\](The $\mathbb{E}$ here signifies expected value.)

So?

At high dimensions “distance” isn’t a very useful metric.

-

Using a unit square neatly demonstrates the equivalency of $\sqrt{r^2 + r^2}$ and $r\sqrt{n}$ where n is the number of dimensions. You can also derive this trivially if you’d rather do it that way:

\[\begin{align*} \sqrt{r^2 + r^2} &= \sqrt{2r^2} \\ &= \sqrt{2} * \sqrt{r^2} \\ &= r\sqrt{2} \end{align*}\]as $\sqrt{r^2}$ is just $r$. ↩

-

a hypercube is the n-dimensional analogue of a square in 2-dimensions or a cube in 3. It adheres to the same basic geometrical rules (the sides are all of equal length and form groups of opposite parallel line segments aligned in each of the spaces dimensions, perpendicular to each other) Wikipedia ↩

-

There are two proofs for this which I’m not going to get into right now. There’s the classic Greek proof: http://mathcentral.uregina.ca/QQ/database/QQ.09.01/rahul1.html and a proof using calculus: An Easy Derivation of the Volume of Spheres Formula ↩

-

$\delta$ can grow no faster/larger than $r$ does so $\delta$ is always smaller than $r$. ↩

-

Where $\alpha$ represents a constant based on the dimensionality $n$. ↩

-

This was originally $10^6$ but I didn’t fancy spending several days waiting for the script to finish running. ↩